Another Father’s Day, which for me is now the tenth that is being observed without my participation. And it’s doubly depressing for me since my father’s last cognizant breaths were taken on the last Father’s Day he was technically alive in 2014. While in a rehab center recovering from a second surgery in two months, a depleted holiday staff erroneously placed him in a normal recovery room rather than the ICU his delicate condition otherwise warranted. He coded, apparently stopped breathing for five minutes and never regained consciousness. It was practically a relief when his body finally gave out about a month later long after his brilliant but tortured brain had.

And if you’ve paid attention to some previous musings about my dad, as a result of his difficulties my own relationship with him was checkered. He both inspired and frustrated me–it was quite clear that he was undiagnosed Asperger’s syndrome and early onset Alzheimer’s at both the onset and sunset of his life. In between, he vacillated between runs of competency and dependence, at least so long as my mother was alive to prop him up–at times literally. Once she passed, he was wholly incapable of self-reliance and ultimately was a burden on my sister and myself. Yes, I’m thankful he didn’t abuse either of us in the traditional and legal sense of the word, but suffice to say neither of us escaped unscathed.

This morning, the NEW YORK TIMES DAILY podcast focused on an episode featuring renowned family therapist Terry Real, who discussed his extensive work with fathers trying to come to grips with their own past traumas that he believes were the roots of whatever family dysfunction they sowed. My own father never had counsel like that–his “therapy” was simply medicinal, and stupefying at that. But I did know his father and I’ve been able to piece back a bit of his own history–enough to confirm that their relationship, while close, wasn’t wholly supportive.

This morning, the NEW YORK TIMES DAILY podcast focused on an episode featuring renowned family therapist Terry Real, who discussed his extensive work with fathers trying to come to grips with their own past traumas that he believes were the roots of whatever family dysfunction they sowed. My own father never had counsel like that–his “therapy” was simply medicinal, and stupefying at that. But I did know his father and I’ve been able to piece back a bit of his own history–enough to confirm that their relationship, while close, wasn’t wholly supportive.

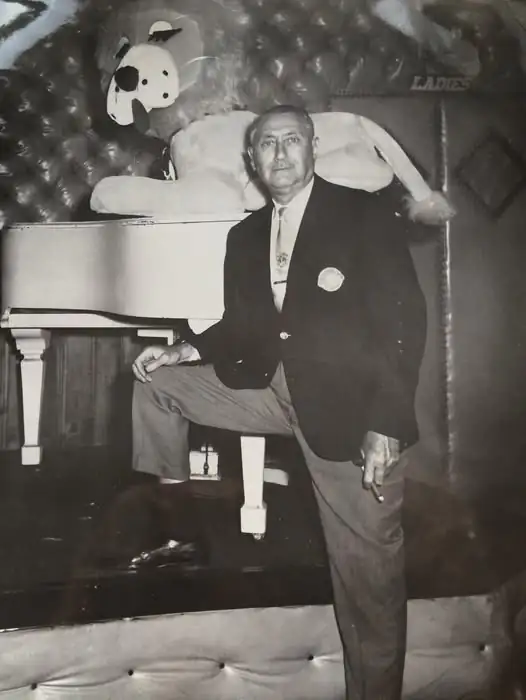

My paternal grandfather had emotional issues of his own; at various points in his life he required hospitalization of his own; though in those days it was never openly referenced. As in the case of my own father’s stays, they were dismissed as “business trips”. But as I peeled back the layers of that particular onion, I also learned a lot more about the degree of pressure my grandfather was under that likely contributed greatly to those trips.

My father’s younger brother Doug was a muser in his own right; he regularly contributed to a Facebook group celebrating the Queens neighborhood he grew up in, the appropriately named Middle Village. Middle-class, middle-of-the-road, and middle-of-the-century. This is how he described my grandfather’s earliest years:

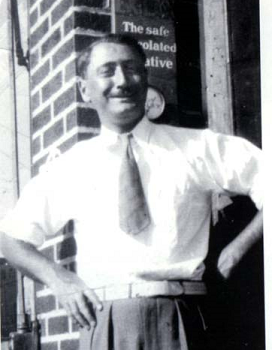

I would just like to say a few words about my dad, David Leblang. In 1924, he had graduated from Columbia University and opened his pharmacy. In those days it was more like a general store in a country town. He lived above the store was on called 24/7 to dispense hand made medicines and first aid. In 1924 you didn’t go to the emergency room-you went to see Dave.

I would just like to say a few words about my dad, David Leblang. In 1924, he had graduated from Columbia University and opened his pharmacy. In those days it was more like a general store in a country town. He lived above the store was on called 24/7 to dispense hand made medicines and first aid. In 1924 you didn’t go to the emergency room-you went to see Dave.

What Doug left out was that he built his business during the height of the Depression, and lived among nine other siblings and their families in a house I barely recall being but couldn’t have been more than 1000 square feet. And his father, a Hebrew school teacher, passed just after the Crash of ’29, putting almost the entire financial burden of the Leblangs on his tenuous shoulders. Stronger men than he have collapsed completely with less stress.

What Doug left out was that he built his business during the height of the Depression, and lived among nine other siblings and their families in a house I barely recall being but couldn’t have been more than 1000 square feet. And his father, a Hebrew school teacher, passed just after the Crash of ’29, putting almost the entire financial burden of the Leblangs on his tenuous shoulders. Stronger men than he have collapsed completely with less stress.

So I began to see my Grandpa Dave in a somewhat more appreciative light. And recently I reconnected by phone with someone I grew up with who apparently has fonder and more detailed memories of my family than I do. And it dredged up a long-dormant memory of when my Grandpa Dave literally saved my neighborhood.

I was an otherwise ostracized kid in a neighborhood filled with ones of similar age. Children can be cruel to someone who needed to have all of his clothes bought at what as derisively known as the “husky” store and whose weight was already coming close to three figures in first grade. Mom had similar DNA, but at least she was a damn good mah jongg player and was friendly with most of my teasers’ moms. Usually, she’d waddle in after midnight flush with a few dollars and a smile on her face, but one night she woke my dad and I up sobbing uncontrollably. When my dad asked what had happened, she paused and said “Merry’s going on a trip”.

What I later learned was the six-year-old daughter of one of our neighbors, a quiet, waifish child named Merry, had contracted meningitis and had been taken to the hospital earlier that evening. The mah jongg klatsch’s response was to keep playing with the alternate. Just before the night’s pot was being parceled out, Merry’s mom called the host. Merry had died shortly after midnight.

Our neighborhood pediatrician was bombarded the next day with visits and calls from panicked parents wondering what to do. His recommend was to get access to a powerful but not easily available antibiotic and get it into the kids’ stomachs as soon as possible. He also warned that it was a particularly vile tasting one that he recalled taking when an outbreak had occurred in his youth. He asked if anyone happened to know a pharmacist. Mom raised her hand.

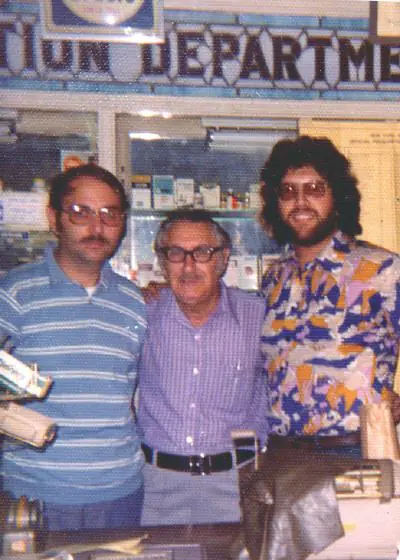

So Dave Leblang called his friends at the Upjohn laboratories in New Jersey that were regularly sending him samples to slip into his customers’ bags and asked for a rush bulk order and for them to mask the antibiotic in a solution that would appeal to six-year-olds. By nightfall, Dave’s battered old turquoise Bel Air with the peach hood sputtered into our neighborhood and a box of chocolate malt-flavored bottles with the label LEBLANG’S PHARMACY prominently featured on them were being handed out to our grateful neighbors. “It’s on me”, said Grandpa. And the crisis past. We all eventually had explained us what had happened to Merry and how important it was that we finish the bottle as prescribed–no ifs, ands or buts. No one complained. And honestly, I recall it tasting a little like Yoo-Hoo.

I may not have become the coolest kid on the block overnight. But at least I started getting invited to a few more birthday parties. And every time my grandfather came to visit our neighbors made sure to stop by and thank him over and over again.

And my grandfather was pretty renowned in his own neighborhood, too. A decade after his 1998 passing at age 93, Maria Candela of the JUNIPER BERRY mailbox-stuffer, penned this biography with highlights like these:

He worked for Riffman’s Pharmacy for 4 years, then bought the business and renamed it LeBlang’s Pharmacy. The store was located at 67-69 78th Street, right on the corner of 67th Drive and 78th street. He ran the store, working long hours and helping when he could. He gave the local kids lollipops and made them laugh. Dave operated his business for 50 years. When he retired at age 70, he didn’t stop his community service. He spent the next 15 years delivering up to 50 Meals on Wheels per day, rain or shine. In the mid 1980’s, he received the Borough President’s Award for Volunteerism.

He worked for Riffman’s Pharmacy for 4 years, then bought the business and renamed it LeBlang’s Pharmacy. The store was located at 67-69 78th Street, right on the corner of 67th Drive and 78th street. He ran the store, working long hours and helping when he could. He gave the local kids lollipops and made them laugh. Dave operated his business for 50 years. When he retired at age 70, he didn’t stop his community service. He spent the next 15 years delivering up to 50 Meals on Wheels per day, rain or shine. In the mid 1980’s, he received the Borough President’s Award for Volunteerism.

At the time the store closed its doors, it was the oldest family-owned pharmacy in the borough of Queens. The spectre of CVS was just beginning to encroach upon the area; for a while, he staved it off if for no other reason than his somewhat older customer base who didn’t own cars were reluctant to schlep up a hill to “The Avenue” during inclement weather. As a younger and more mobile generation matured, having a country doctor in an urban shtetl became less desired.

At the time the store closed its doors, it was the oldest family-owned pharmacy in the borough of Queens. The spectre of CVS was just beginning to encroach upon the area; for a while, he staved it off if for no other reason than his somewhat older customer base who didn’t own cars were reluctant to schlep up a hill to “The Avenue” during inclement weather. As a younger and more mobile generation matured, having a country doctor in an urban shtetl became less desired.

So yeah, I’m proud of my grandfather. And I honestly hadn’t thought about him all that much recently. I had a far closer relationship with my maternal grandfather, the British-born, horse racing and soccer-loving cherub that always made us laugh. But in remembering what I did, not to mention going back over my uncle’s passionate musings, I was reminded that I owed him at least the honor of recall, and maybe a little more respect.

Maybe you’ve got a family member you’ve forgotten over time. It happens. Today’s a good day to at least sift through the rubble in your mind and see who you may have forgotten. And if no one comes to mind, feel free to salute Dave Leblang.

Happy Father’s Day.

Until next time…