Back in days where the word tech was most prominent following the name of a university in Georgia or Texas or a small college for geeks on Long Island there was a derogatory analogy applied to fans of the New York Yankees that rooting for them was like rooting for U.S. Steel. That was in a century where the Yanks had more than one title–not the one we’ve now somehow made it one-fourth of the way through intact. In this one, the analogy might more appropriately be this: rooting for the Dodgers is like rooting for Netflix.

On just about every quantitative and qualitative metric of consequence, including both award and stock price, Netflix dwarfs its direct competition. That is with the exception of how it plays to the cold-hearted world of advertisers, a path that even they have had to pivot to given that when you’ve essentially maxed out the North American market subscriber-wise and even they have a limit on what they can charge them. Hence the obsession with making themselves as appealing as possible to that world, facts notwithstanding.

On just about every quantitative and qualitative metric of consequence, including both award and stock price, Netflix dwarfs its direct competition. That is with the exception of how it plays to the cold-hearted world of advertisers, a path that even they have had to pivot to given that when you’ve essentially maxed out the North American market subscriber-wise and even they have a limit on what they can charge them. Hence the obsession with making themselves as appealing as possible to that world, facts notwithstanding.

We’ve mused about this reality many times before, most starkly roughly three years when old school media reminded that when it came to ad-capable audiences as traditionally defined by third party measurement even their hits were no more popular than a newscast in a mid-sized diary market. And when Prime Video decided to pivot their entire subscriber base to ad-inclusive as a default rather than leaving it up to theirs to opt in they developed a huge advantage on that metric–not that they’ve been able to fully take advantage of it since their programming efforts have largely been nowhere near as popular as Netflix’s.

So with the countdown to the 2026-27 upfront (gee, we ARE getting deep into this century, aren’t we, kids?) under way and with Netflix’s actual growth on those archaic metrics nowhere near keeping pace with how they’ve paced with awards and platform viewership–let alone Wall Street’s expectations–this week they decided to redefine how said success is determined. VARIETY’s Brian Steinberg was among the less jaundiced who reported on this yesterday:

Netflix wants to throw another type of yardstick into the ever-evolving pile of audience-measurement tools. The streaming giant intends to institute a new measure for advertisers that tabulates how many of the 190 million monthly active viewers on its ad-supported tier see a specific commercial, the company’s president of advertising, Amy Reinhard, announced Wednesday. Netflix defines monthly active viewers as “members who have watched at least one minute of ads on Netflix per month multiplied by the estimated average number of people within a household,” a figure derived from Netflix’s own research.

Netflix wants to throw another type of yardstick into the ever-evolving pile of audience-measurement tools. The streaming giant intends to institute a new measure for advertisers that tabulates how many of the 190 million monthly active viewers on its ad-supported tier see a specific commercial, the company’s president of advertising, Amy Reinhard, announced Wednesday. Netflix defines monthly active viewers as “members who have watched at least one minute of ads on Netflix per month multiplied by the estimated average number of people within a household,” a figure derived from Netflix’s own research.

In past years, Netflix based its measurement on account profiles, or users, rather than the number of people in a home that subscribes to its service. In May, the company said its ads reached 94 million monthly active users, compared with 70 million in November of 2024. The switch to members of a household, instead of just an account, will clearly boost the audience numbers Netflix touts to potential sponsors – though it remains to be seen how much credence Madison Avenue will grant the new metric.

Now Netflix has been able to sell many observers, especially the trade press, on how generous and transparent they are with sharing actual data–unlike their far more opaque and less popular competitors. We’ve previously mused about that, with perhaps a bit more persnickety an attitude about said transparency than others who have made it a habit and even a cottage industry to parse the tens of thousands of programs that produce essentially live-plus-180s with a self-determined and ever-pivoting baseline that measures billions of hours rather than average minutes viewed. Because it sure SOUNDS impressive to talk about numbers that big. It’s worked for Doctors Evil and Oz (yes, they are two separate lost souls), hasn’t it?

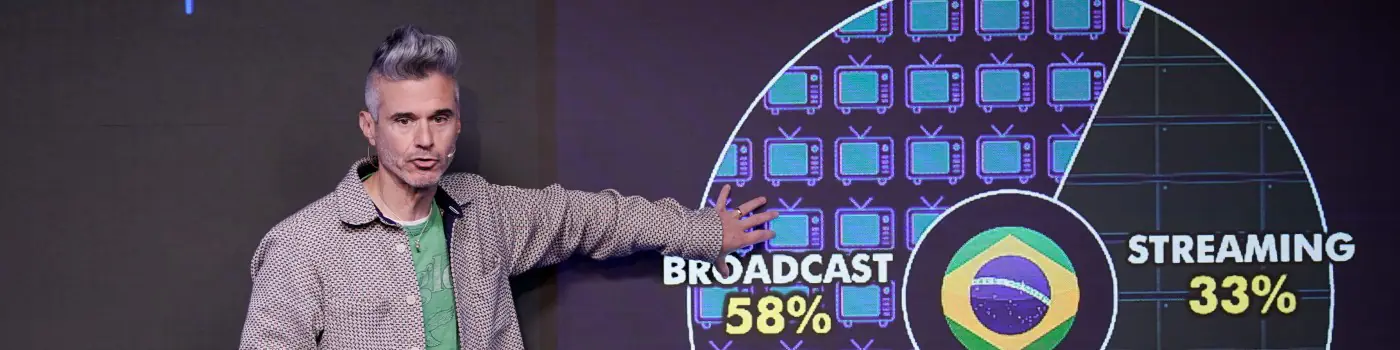

But to the more informed and disbelieving folks out there who digested this latest data conflation including moi, we’re not quite buying into all of it. The ever-loquacious Evan Shapiro, who’s perhaps feeling his oats a bit more than usual with his beloved Philadelphia 76ers off to a surprisingly good start, took to LinkedIn to weigh in as only he can. He even got me to offer a comment because, realist that I am, I know when it comes to reach his megaphone is a lot closer to Netflix’s than mine:

But to the more informed and disbelieving folks out there who digested this latest data conflation including moi, we’re not quite buying into all of it. The ever-loquacious Evan Shapiro, who’s perhaps feeling his oats a bit more than usual with his beloved Philadelphia 76ers off to a surprisingly good start, took to LinkedIn to weigh in as only he can. He even got me to offer a comment because, realist that I am, I know when it comes to reach his megaphone is a lot closer to Netflix’s than mine:

One question: when did Netflix install cameras or ask its subscribers to regularly log in to at nest verify their “estimated vpvh” was indeed accurate on a content level? I guess that’s why they’re called estimates. Now I know why they’ve done through three different research heads in the last three years.

If his video snark wasn’t clear, his response to me made it crystal clear where he stands:

Steve Leblang The definition of MAV is a joke – without a punchline.

Aside from the very valid point he raises about how Netflix has quietly used the one-minute threshold viewing of CONTENT–not necessarily ads–as its baseline, on the heels of that came this report from TV TECH (you see how that word crops up more frequently in this century)’s George Winslow that calls into further question what else people may be looking at when ensconced in the walled gardens that streaming platforms are:

Despite all the hype around AI and long-standing efforts to improve content discovery, a new Gracenote study indicates that the problem of finding something to watch on streaming services is not only a major annoyance. It is actually getting worse.

The new Gracenote study “2025 State of Play” surveying consumers in the U.S., U.K., Germany, France, Brazil and Mexico, finds that nearly 33% of streaming users feel content and service fragmentation negatively impacts their TV experience. Among the 25-34 age group, that concentration rises to 40%. Despite general love for streaming among consumers in different countries and age groups, 45% say the streaming experience is overwhelming.

The new Gracenote study “2025 State of Play” surveying consumers in the U.S., U.K., Germany, France, Brazil and Mexico, finds that nearly 33% of streaming users feel content and service fragmentation negatively impacts their TV experience. Among the 25-34 age group, that concentration rises to 40%. Despite general love for streaming among consumers in different countries and age groups, 45% say the streaming experience is overwhelming.

One key issue is content discovery. The longer it takes for viewers to find something to watch, the less enjoyable the experience becomes. On average, consumers globally spend 14 minutes searching for what to watch. In the U.S., the amount of time is 12 minutes, up from 10.5 minutes in mid-2023. French viewers spend a whopping 26 minutes searching for content, an amount of time equal to the length of an entire program episode, the researcher Gracenote, a unit of Nielsen reported.

And since many of the countries surveyed match up with those who are capable of receiving Netflix’s advertising, that’s a study that were I Amy Reinhard or one of her lackeys I’d be at least paying attention to. Assuming any of them are staying around in their jobs long enough to actually act upon it.

None of this is to suggest that Netflix isn’t still far more an 800-pound gorilla more than capable of making further headway in an increasingly splintered landscape. Steinberg even rounded out his report with more of Netflix’s party line about their continued expansion into live, ad-supported content apart from bingeable scripted fare. And yes, I’d rather be in their camp than, say, HBO Max’s, because the chances I’d actually be able to present in the 2026-27 upfront as a paid employee are a LOT better.

But continuing to try and dance around exactly what level of dominance they have to a more objective constituency shouldn’t be where their efforts are concentrated. A lot of us are watching this, if not their ads.

Until next time…